World’s largest flying boat ever built makes first and final flight

GIGANTIC FLYING SHIPS

***

In 1942 the United States and her Allies battled against the Axis powers. Packs of Nazi U-boats patrolled the oceans, sinking Allied vessels at a ferocious rate and threatening vital supply lines. By July, 681 ships had been lost to the submarine peril in just seven months.

When American industrialist Henry Kaiser had taken up ship building in 1940, he revolutionised the industry with his ‘Liberty Ships’. Even though he had reduced the build time of a 10,000-ton freighter from 355 to just 48 days, in 1942 this was not enough. The submarines torpedoed vessels faster than replacements could be launched.

Kaiser proposed giant flying boats should carry cargo over the sea out of the reach of enemy torpedoes. At a Liberty Ship launch he announced his intentions: ‘Our engineers have plans on their drafting boards for gigantic flying ships beyond anything Jules Verne could ever have imagined.’

Although Kaiser knew ships, he had no aviation experience. His approaches to the established aircraft companies failed. They believed the idea impossible. There was only one man with the vision and resources to bring the idea to fruition: billionaire businessman Howard Hughes.

An eccentric Hollywood moviemaker with a talent for aviation, Hughes was born in Texas in 1905. Fiercely private, he shunned the limelight but enjoyed the company of screen starlets. After directing a series of successful films, his focus turned to aviation. A talented engineer, Hughes proved himself to be a skilled test pilot. In 1932, he set up the Hughes Aircraft Company at Culver City, CA, to manufacture his unique designs.

The prospect of building the world’s largest aircraft intrigued Hughes, and Kaiser’s enthusiasm for the project was infectious. The two men agreed that if Hughes designed and built the prototypes, Kaiser would utilise his shipyards to build a fleet. They won a government contract for $18million to produce three prototype aircraft.

A HERCULEAN TASK

***

To take a new aircraft from the drawing board to the skies takes years. The contract allowed just 24 months and Kaiser was boasting they would do it in ten. Time constraints were not the only challenge, leading both men to suspect the government was against their project. They were contracted not to compromise the war effort and forbidden from attracting experienced personnel away from other aircraft companies.

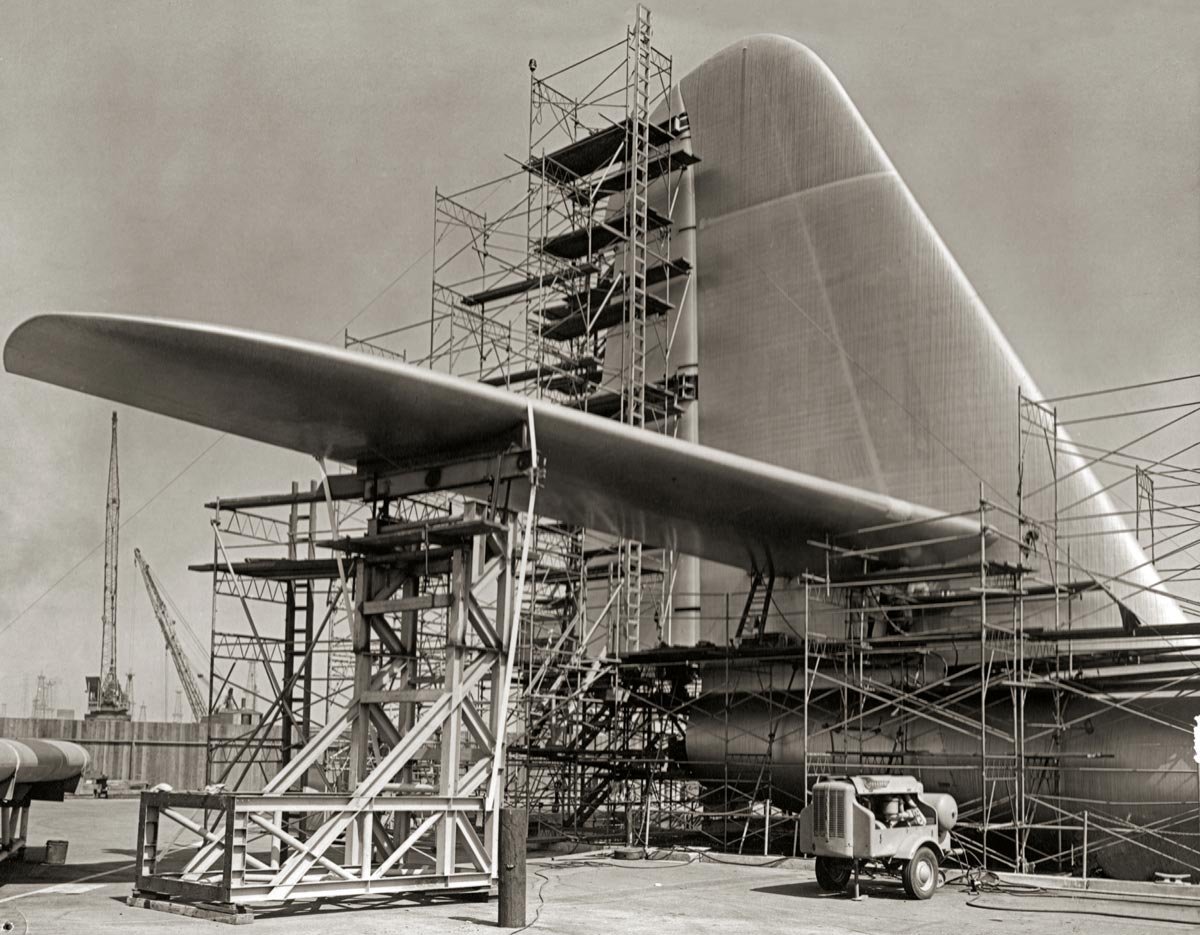

Worse still, they were not allowed to use materials deemed scarce, such as aluminium. The great flying boat would have to be constructed from wood, a feat that many considered impossible. Watchmakers and aircraft manufacturers alike know that wood is a difficult material. To counter variations in density, each piece used in the aircraft was weighed and matched to an opposing part, to maintain the correct overall weight and balance.

Hughes developed a technique called Duramold. Criss-cross layers of wafer thin birch veneers were bonded together with resins to create a strong and beautiful skin that required no rivets. The entire surface was sanded down by hand and finished with layers of rice paper and silver aluminium paint.

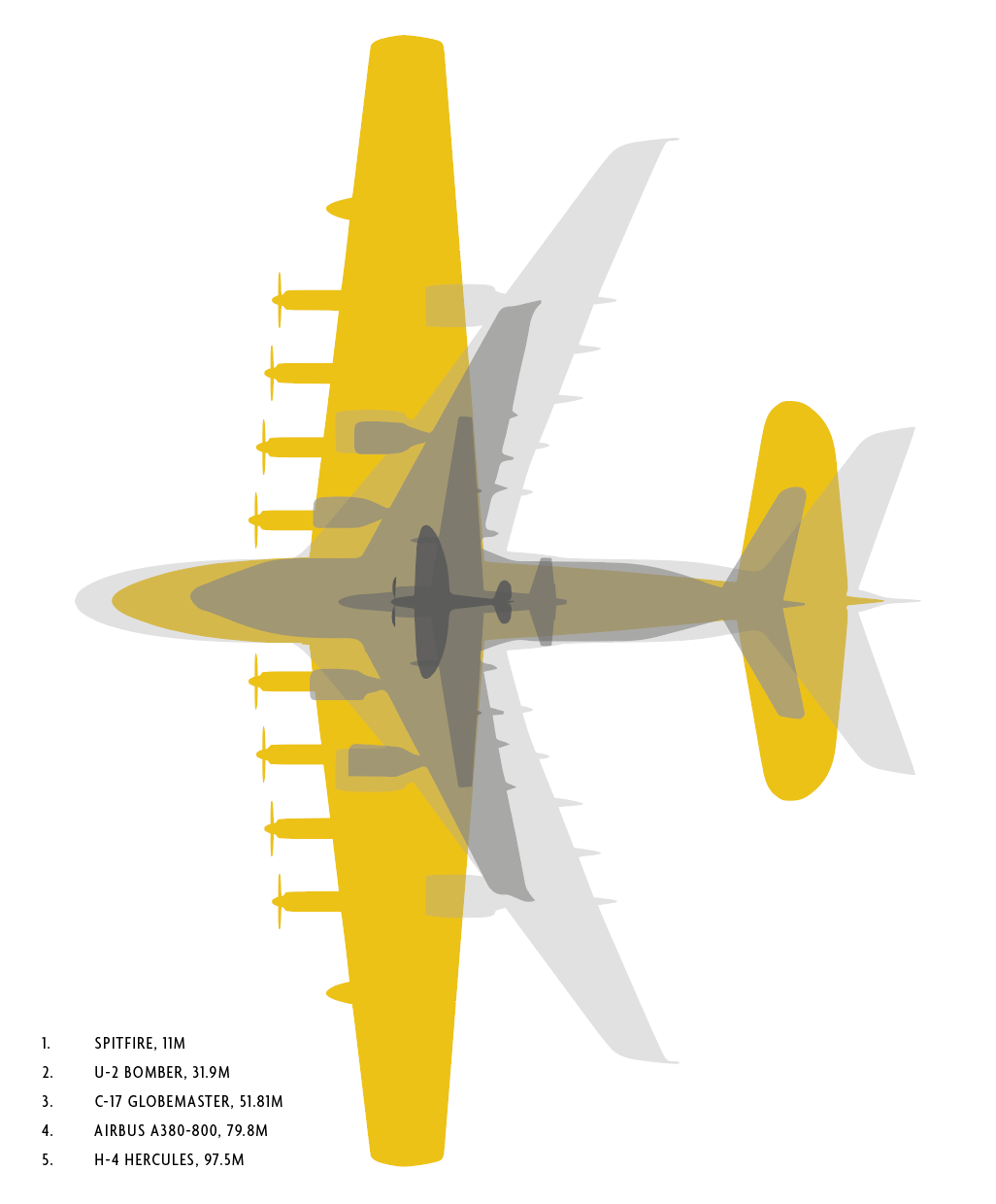

The Hercules was more than double the size of any contemporary aircraft. Its wingspan was 320 feet, longer than the Statue of Liberty. A grown man could easily walk inside its 11 feet deep wings. The tail was comparable to an eight-storey building. The wings housed eight Pratt & Whitney R4360 28-cylinder radial engines. They produced 24,000 horsepower to lift the 400,000lb fully loaded airframe. With a 3,000-mile range and cruise speed of 200 mph, the Hercules was designed to carry 400 troops or two Sherman tanks safely across the ocean.

The sheer scale of the aircraft presented unique challenges that Hughes solved with innovative solutions. During construction, normal workbenches were far too small to be useful. So the moviemaker used film projectors to display plans onto the factory floor, allowing his engineers to manufacture parts to size.

The Hercules pioneered advances in control and power systems that paved the way for future large aircraft types. The fabric control surfaces were vast. The ailerons alone were 140 feet long. The equivalent strength of 200 men would be required to move them in flight with traditional mechanical cables. So Hughes designed the first hydraulically actuated control system.

The miles of electrical cables presented a weight problem, so the Hercules pioneered a 120v DC electrical system, which enabled the use of smaller cables, giving a 75% weight saving overall. A series of intercom radio points were used to enable immediate communication with engineers on board and counter the distances inside the aircraft.

The interior featured two decks connected by an elegant spiral staircase. The cockpit had large windows and reclining padded chairs for the pilot and flight crew. With two generators bolted to the floor of the flight deck, the air on board risked being less than fresh so Hughes had a pipe installed to pump fresh air directly over the left hand side pilot’s seat, where he would be seated.

Amongst Hughes’ many aviation feats was a record-setting global circumnavigation in 1938. Concerned about ditching at sea, he prepared his aircraft with 80lbs of ping-pong balls positioned in the wings and fuselage to keep the aircraft afloat. For the Hercules, he scaled this idea up and used nets of inflatable beach balls stowed in the fuselage and wings.

AN EPIC JOURNEY

***

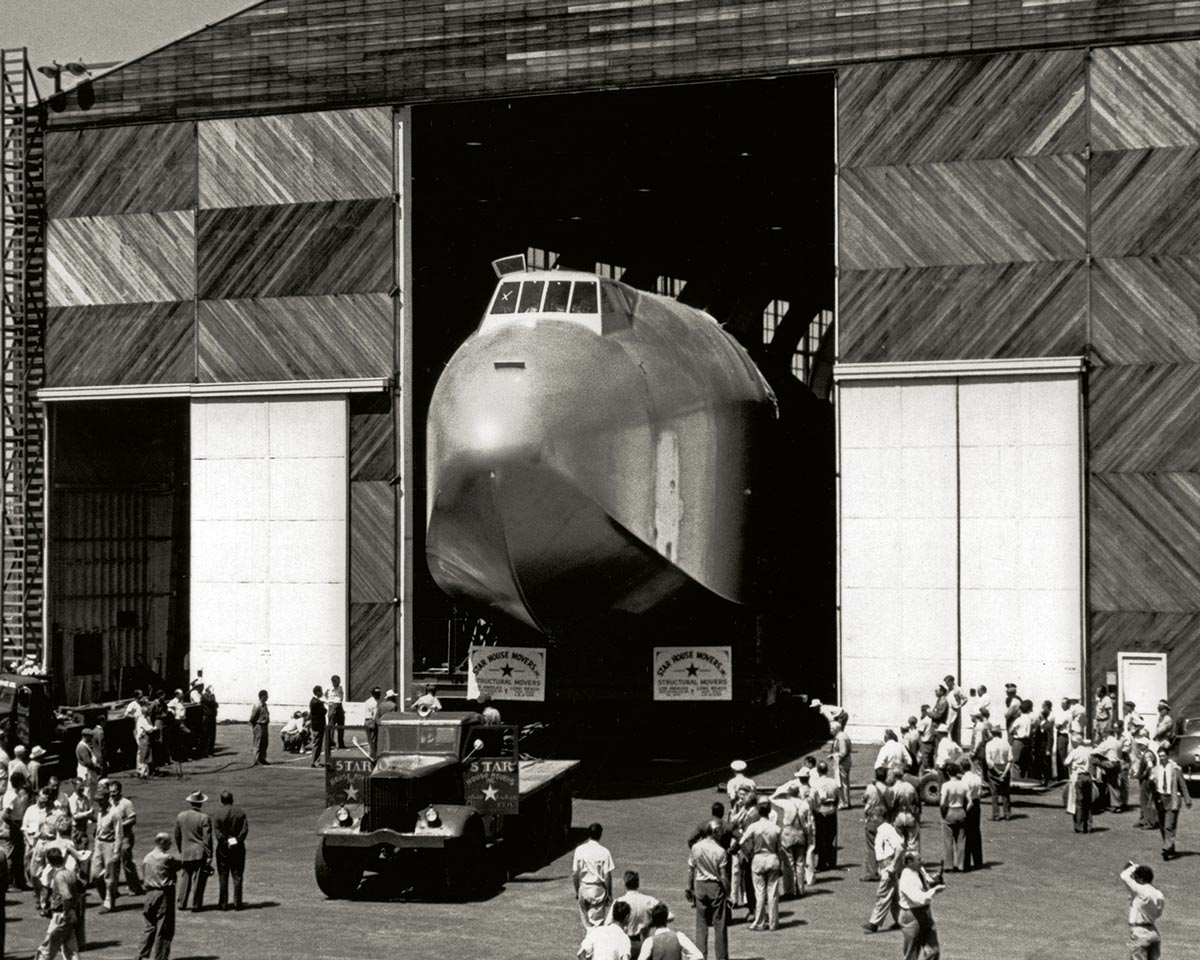

Progress was slow. Hughes was a legendary perfectionist who involved himself in every decision, no matter how small. The Hercules was not his only project. As 24 months came and went, Kaiser withdrew in frustration. The airframe was not ready for testing until June 1946 and that required moving from Culver City to the ocean.

The move was a major operation. Crews went ahead to prepare the route for this giant cargo, taking down over 2,000 telephone and power cables. The hull, wings, tail and control surfaces were positioned on enormous trailers. Crawling along at 2mph, the convoy took two days to complete the 28-mile journey to Terminal Island, Long Beach. School children were released from lessons and crowds lined the roads to witness the unusual sight.

The Hercules was nearing completion, but any strategic requirement for the huge flying boat was gone. The Allies had long since turned the tide and won the war. Questions were asked and the voices critical of Hughes grew louder. In the summer of 1947, he was called to a Senate hearing to be accused of wasting government funds.

Although contracted to produce three aircraft, Hughes had not yet finished one. He argued that building an aircraft on this scale had pushed the boundaries of aviation design. He had made discoveries that would prove vital in future aircraft manufacture but conceded that the process was slow:

“If I made any mistake on this airplane it was not through neglect. It was through supervising each portion of it in too much detail… I am by nature a perfectionist, and I seem to have trouble allowing anything to go through in a half-perfect condition. So if I made any mistake it was in working too hard and in doing too much of it with my own two hands.”

Hughes vigorously defended his project and reputation. The Hercules had cost $25million so far, which included $7million of Hughes own money:

“I put the sweat of my life into this thing. I have my reputation rolled up in it, and I have stated that if it was a failure I probably will leave this country and never come back, and I mean it’.

During six days of intense questioning, Hughes won the support of the press and the public. The hearing collapsed into a media spectacle and was permanently adjourned. Wounded by a Senator’s accusation that his ‘flying lumberyard’ would never get airborne, Hughes devoted all his attention to completing the project. Work commenced 24 hours a day and a date was set for taxi trials.

MAKING SURPRISES

***

Hughes organised the taxi trials like a Hollywood premiere. VIPs, starlets, photographers and the media were all in attendance. On 2 November 1947, crowds of onlookers lined the shores watching the Hercules taxi out into the harbour in blustery conditions.

Keeping a sharp look out for debris in the water, Hughes completed one low speed taxi run, before positioning into wind for a second faster run. The Hercules rose up on to the step, slicing across the wave tops. Above the rumble of the engines, those on board could hear the water slapping off the hull.

When the second run was safely completed, a correspondent asked Howard if he intended to fly that day. ‘Of course not’ he replied. The pressman asked to go ashore to file his copy. A small tender came alongside to collect him and others who did not want to be ‘scooped’ on their headline-grabbing story.

A radio newsman remained on board recording a broadcast: ‘This is James McNamara speaking to you from aboard the Howard Hughes two hundred-ton flying boat, the world’s largest aircraft. At this moment we speak to you from the spacious flight deck. This mighty monster of the skies is slowly cruising along a northwest course in the outer Los Angeles harbour.’

‘Howard, do you have time at the moment to explain for our radio listeners exactly what you’re doing – the operation?’

‘Yeah,’ said Hughes, ‘We’re taxiing downwind very slowly to get into position for a run between the entrance to Long Beach Harbor and Myrtle Beach and San Pedro. It’s about a three mile stretch there and we’re gonna make a high-speed run in that direction. The wind is changeable – it’s been changing all day – but it’s not too serious.

‘Howard, I didn’t hear you,’ said McNamara, ‘There’s so much noise here. But did you tell our listeners the speed you achieved on the last run?’

‘That was right around ninety miles an hour. We were well up on the step and the airplane could have lifted off easily if I’d just pulled back on the control, I’m sure. But we have so many mechanical devices in this ship right now that I wanta check a few of ’em out a little bit before we try anything like that.’

Hughes then ordered his flight engineer to ‘lower fifteen degrees of flaps’. Some on board realised this was the take off setting for the giant flying boat. As he pushed all eight throttle levers forward, McNamara called out the building speeds: ‘It’s fifty. It’s fifty over a choppy sea. It’s fifty-five… More throttle… It’s sixty. It’s about sixty-five. It’s seventy’. The water rushed against the hull. As McNamara called ‘Seventy-five’ the noise ceased. The Hercules was airborne.

As the silver behemoth lifted above the waves, the crowds began to cheer. Hughes flew the ship low level for a little under a mile and a little less than a minute before gently executing the smoothest of landings. The Hercules had flown and his critics were silenced. McNamara asked him, ‘Howard, did you expect that?’. Hughes’ response was cryptic: ‘I like to make surprises’.

It was the first and the last flight of the Hercules. For the remainder of his lifetime, Hughes never admitted whether he intended to fly. He spent millions of dollars keeping the aircraft in airworthy condition until his death in 1976. The Hercules was exhibited at Long Beach, before making one final journey in 1993 to its current home in Oregon.

The Hercules remained the world’s largest aircraft for over seventy years. It is still the largest flying boat ever built. Hughes wanted to be remembered for his contribution to aviation. Today the aircraft is expertly cared for by the Evergreen Aviation & Space Museum and visitors to their McMinnville site, near Portland, can climb aboard the Hercules, a colossal legacy to the daring and determination of its inventor.

THE BREMONT H-4 HERCULES

***

The H-4 Hercules and, to a degree, Howard Hughes’ genius was defined by one minute. One minute of flight on 2nd November 1947. In that time Howard Hughes’ vision for the greatest aircraft ever built was vindicated. It’s fitting therefore that the aircraft is being commemorated by a timepiece of this stature. Limited to just 300 stainless steel, 75 rose gold and 75 platinum pieces, the Bremont H-4 Hercules is a sublime fusion of micro-engineering, watch design and aviation history. The 25 jewel Bremont BWC/02 movement is based on the original proprietary automatic BWC/01 calibre built in partnership with movement house, La Joux Perret, and is housed in a beautifully finished 43mm case. The new slate grey coloured BWC/02 movement has GMT functionality, along with hours, minutes, a smaller non-hacking seconds hand at 9 o’clock and the date at 6 o’clock.

View the H-4 Hercules Collection Here